By Frances Casey, Project Manager

Last Saturday, the 2013 Chelsea Flower Show came to an end. It was a week during which exhibitors celebrated the centenary of the event, which was first held at the Royal Hospital grounds in Ranelagh Gardens in 1913. The 2013 show was in fact the 92nd Chelsea Flower Show, rather than the 100th, as the event was cancelled during the First World War in 1917 and 1918, and also for the duration of the Second World War.

Poster for the RHS War Relief Fund, 1916 (©IWM ART PST 10965)

In RHS Chelsea Flower Show: A Centenary Celebration, the illustrated book published to commemorate the history of the show, the Royal Horticultural Society (RHS) historian Brent Elliott lists some of the names of the horticultural firms that exhibited in the first show of 1913. These include Notcutt Nursery, founded in 1897 in Suffolk, and particularly famed for its trees and shrubs.

The 1914 Chelsea Flower Show was held three months before the outbreak of the First World War. Notcutt Nursery was busy that year, and in April had exhibited at the RHS fortnightly meeting in Westminster, at which ‘a much admired shrubby plant certificated was Mr Notcutt’s Prunus Blirisana (The Times, 8th April 1914, pg 11).

In 1915 however, the presence of the war was felt at Chelsea, and the Royal Horticultural Society used the show to seek funds for the newly founded RHS War Relief Fund. This fund had the specific purpose of raising money to buy seeds, plants, trees and equipment to replant the already devastated gardens and countryside of France, Belgium, Romania and Serbia. Funds and supplies were to be distributed as and when the war ended.

In 1916, at the last Chelsea Flower Show to be held during the war, changes to Show included the absence of the great tent, ‘for the reason that the active young men who erected it and climbed the big poles are now in the Navy’ (The Times, 23rd May 1916, pg 11). The loss of men from the estate gardens and nurseries to war service contributed to the cancellation of the Show in 1917 and then again in 1918.

It is possible that some of the gardeners, growers and staff of Notcutt Nursery who attended the first Chelsea Flower Shows in 1913 and 1914 and the RHS show at Westminster in the Spring of 1914 are among those commemorated by the Notcutt Nursery war memorial, which is a sundial in a garden of remembrance at the present day nursery. This memorial records the loss of six members of staff during the First World War and two during the Second World War.

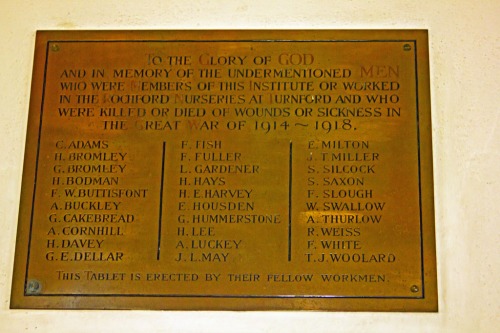

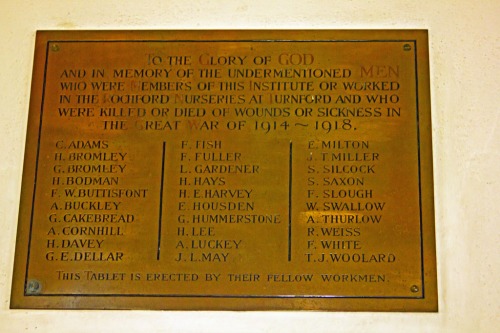

Rochford Nurseries (IWM WMA 63530 ©Liam Gillespie, 2012)

The memorial to the Hertfordshire floral nursery of Thomas Rochford in Turnford lists the names of thirty members of the Turnford Institute and Rochford Nurseries staff who were ‘killed or died of wounds or sickness’ during the war. The nursery had competed in the Roses category at the Chelsea Flower Show of 1916. Goldsworth Nursery, founded in 1790 in Woking, exhibited regularly at the Rhododendron Association shows at RHS Westminster. The nursery lost eighteen men.

Country estates also suffered from the loss of their garden staff. The memorial at Backwell Hill House, near Bristol, commemorates three casualties. Christopher George Ball, ‘second gardener on this place’ and William Henry Lock, ‘garden boy on this place’ are named alongside William Patrick Garnett, the son of the owner of Backwell Hill House.

The Thunderbox, Heligan Gardens (IWM WMA 63622 ©Heligan Gardens Ltd)

In Cornwall, the gardens of Heligan House are maintained today as a memorial to the gardeners of the estate who went to war. Visitors to the garden can still come across The Thunderbox, the garden toilet and store, which bears the signatures of garden staff under the portentous date of ‘August 1914’.

The memorials of the RHS School at Wisley in Surrey and the Royal Botanical Gardens of Edinburgh and Kew show the loss of a generation of horticultural talent to the First World War. Edinburgh lost twenty men, whilst at Kew, thirty seven members of staff are listed as killed above the Kew Guild motto ’Floreat Kew’ (Flourish Kew).

At ZSL London Zoo, two staff members, Albert Staniford and Robert Jones, are commemorated with the profession ‘gardener’. Professional gardeners are also named on community memorials, such as that in Elie, Fife, where two casualties hold the profession of ‘gardener’. At The Kings School in Canterbury the word ’Hortulani’, Latin for gardener, is next to the name of Harry Rogers.

Royal Botanic Gardens Kew (IWM WMA 12518 ©IWM 2013)

Although the First World War led to the loss of many RHS student gardeners and nursery and estate staff gardeners, the RHS vision of rejuvenation by horticulture greatly assisted the replanting of the countryside and provided food supplies in France and Belgium after the war. The RHS War Relief Fund distributed seeds, saplings and grown trees which were transported by the British Red Cross from 1919 onwards, and many of the trees planted at this time are still growing today.

Notcutt Nursery also returned to exhibit at the 1921 RHS Show of British-grown fruit in Westminster. Despite the nursery’s staff losses during the war, continuity was shown as the nursery was awarded the trade group Silver medal for fruit, where ‘the chief strength lay in the pears, which were exhibited in great variety.’ (The Times, 5 Oct, 1921, pg 8).